Orchestration notes for including Chinese Orchestra

Last week during Hwa Chong’s 95th Anniversary concert week, I received some questions about orchestration for Chinese Orchestra (CO) when combined with western instruments. I must first admit I’m not an expert, but I do need to take notes for my future self if such projects comes about again. The following is my experience based on triangulating my childhood experience, interactions with members of Dingyi (鼎艺), one of the leading CO ensembles in Singapore, and members of Hwa Chong’s JC and High school CO players, and assumes you know what is CO is already like today.

Intonation

The layman stereotypical view of CO is that it is out of tune, and that is not very far from the truth. The problem is multifold.

First there are really difficult instruments to play well that dominates the sound scape – such as the Suona. The lack of intonation accuracy of the dominant sound provide a disincentive for the rest to stay in tune. Yangqin and the plucked strings (e.g. Pipa) tune individual strings before hand and ignores intonation thereafter (most are fretted). Instruments like the Sheng undergo week long tuning of pipe to pipe, requiring tremendous efforts.

That leaves the Dizi and the bowed strings (Erhu etc.) which can be tuned before and during performance. Most of which does not know where to start. If there’s one last bastion of pitch accuracy that would be the imported cello bass section that provides a reference.

Second is the introduction of the western concept of harmony into the mix. When we combine CO instruments into western strings, winds or brass, they finally got the luxury of pitch of reference, but also the challenge of complex harmony that can be performed correctly only when all pitches of the chord plays their part. I’m not talking about clusters here, just try a diminished 7th chord and compare it to a normal minor 7th chord. Tri-tones anyone?

In band, we teach methods like lowering the 3rd, 7th, raising 5th and so on to make instruments blend into the overtones of one another. This is hard tedious training that hardly any CO goes through. At the end, we did normal major and minor chords in a single key well, opportunities to present pentatonic scales were seized, but anything more sophisticated like bar to bar modulation was struggled through.

And finally, in the tradition of CO as well as many folk musical groups, melodic material takes precedence over harmonic material. CO player spend a lot more time learning the right technique to get their appoggiaturas and acciaccaturas to sound tasty and linger on every melodic phrase given, which brings me to the next point:

Rhythm

Most young players take to heart that when it’s their chance to shine, they will unlock their courage and hold the entire ensemble in ransom – Listen to My Great Melody. I’m not sure if the instructors will give way to them, but it is disruptive to the rest of the accompaniment.

We kept the percussion right in the middle despite the large orchestral setting to prevent this from happening, but there were parts of the music where no percussive rhythms were given and solos went on and took their own tempo. Culture, ego and even instrument design (some instruments cover the musician’s line of sight with conductor) contributed to the problem.

But that’s not all – there’s also a lack of concept of impulse, or a steady momentum. This is much harder concept to teach and many CO or band instructor alike resort to beating the conductor stand (till it breaks) or have a snare drum subdivide the tempo. Orchestral players would appreciate this issue, as many famous conductor don’t give the player tempo, relying on the ensemble’s own musicianship to reinforce one another. Borrowing a quote from Lim Yau, “when you borrow time to emphasise something, you must return it the next instance”, that’s doing a rubato line in tempo.

Timbre and Balance

Apart from challenges of the show being outdoors, there’s also a challenge of balance of individual section timbres. For example, Dizi and Flutes cannot play parallel harmonies (it won’t “ring”), 1 Suona is 3 times the volume of 1 Trumpet, vibrato on Violins and the Huqins produces different effects, even the attack and intensity of a Paigu is easily disturbed when matched with a western toms.

The responsibility here lies more with the composer than the performer (see below).

Notation, Form, Style, Dynamics, Articulation

The rest are less a CO issue and is more general care for young players. Jianpu is a complete notation system that can capture 99% of what’s going on a manuscript. All young players require training to bring out large dynamic range and correct articulation. The form and style is pretty much subject matter dependent and will require everyone to have an open mind when performing.

Orchestration Tips

So depending on your project, you might be asked to showcase some CO instruments accompanied by a western orchestra or symphonic band, as such:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_detailpage&v=uVQa6k7LchU#t=37

Or combined the entire CO into the orchestra.

1. Layout: After experimenting with a few layouts, I found grouping by instrument sections (winds, brass, percussion, strings) as still the easiest for both the composer and the conductor. You can go by instrument range to order them, or type (e.g. reeds together). This will force you to think of the individual sections and not which group they came from, otherwise if you’re writing a separate movement CO only better to just take out the rest and keep it clean.

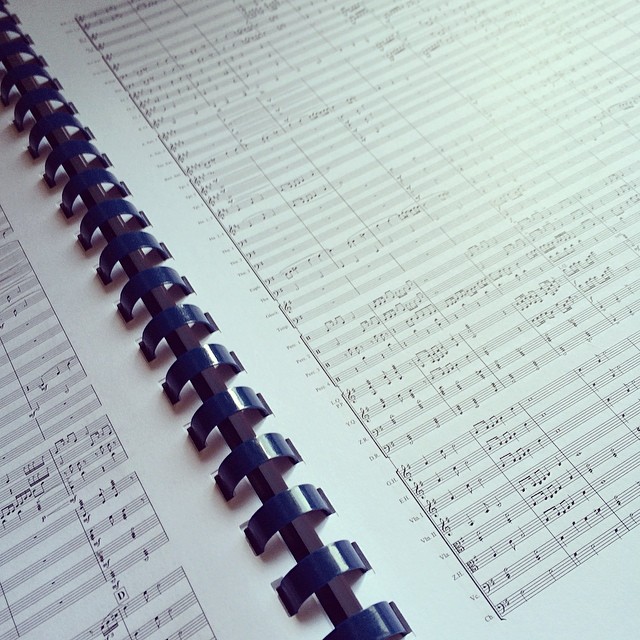

Here’s my sample (this combines western strings, symphonic band, CO, and a choir)

Woodwinds – by type/range

Bangdi

Qudi

Piccolo

Flute 1

Flute 2

Oboe

Gaoyin Suona

Zhongyin Suona

Gaoyin Sheng

Zhongyin Sheng

Diyin Sheng

Bassoon

Clarinet 1

Clarinet 2

Clarinet 3

Bass Clarinet

Alto Sax 1

Alto Sax 2

Tenor Sax

Baritone Sax

Brass – regular

Trumpet 1

Trumpet 2

Trumpet 3

Horn 1, 3

Horn 2, 4

Trombone 1

Trombone 2

Trombone 3

Euphonium

Tuba

Percussion – as needed (all percussion 1 to 4 has a mixture of western / chinese instruments)

Timpani

Glockenspiel

Drum Set

Percussion 1

Percussion 2

Percussion 3

Percussion 4

Plucked Strings – by range

Liuqin

Pipa

Yangqin

Zhongruan

Daruan

Choir – regular

Soprano

Alto

Tenor

Bass

Bowed Strings – by range (sort of)

Gaohu

Erhu

Violin 1

Violin 2

Viola

Zhonghu

Violoncello

Contrabass

And you just write like you’re writing Beethoven Symphony #9. If there’s only band and CO, the layout still works but you must be careful that chinese strings will need a lot more harmonic support from the reeds.

If you’re writing for solo or a small ensemble that features them, keep them together (middle or top) so that the conductor doesn’t have to hunt for them.

2. Style

No matter what you’re trying to write, your music is going to sound more “chinese” when CO instruments are added. Thus, it’s best to capitalise on this asset.

However, when you feature these instruments, remember the challenges I listed above. Unless they are mic-ed, don’t put too much accompaniment. Unless you’re working with a well pitched instrument, don’t introduce running harmonies. Unless you really want an open rubato passage, always hint rhythm (e.g. basses or percussion) to keep everyone together.

Much like how one learn Jazz, you’ll ask find it instructive to listen to some of the masterworks in CO and lift passages into your work, and then massaging them into your material. One has to find that “lick” (sorry for the lack of a better word) for the instrument you’re trying to feature, whether is that wavy thrill on the Dizi, or that soulful portamento on the Erhu, and so on. It will not sound cliche if used properly.

When in doubt – go for unisons and simple rhythm to keep the spirit high. Don’t forget about the percussion which can add a huge palette of colour to your already European + Latin American (+ African) percussion instruments.

3. Sweat the details

Once you got started and have an idea (or even before), you need to ask questions like – how many players do you have? What kind of instrument do you have? How large a range can you master?

Theory books on these instruments can only get you started, but due to the shorter history of the CO (it was only formalised only in the 1950s and still changing) and the wide variety of instrument makers, and varying budget on part of the player or organisation, you milage will vary. Let me go through in detail:

Dizi: Advanced players will have multiple Dizis in a variety of keys), but please be kind on the keys. Most COs have not invested in the Xindi (the chromatic brother that doesn’t sound as authentic), and half hole notes are hard to get right. Many young players can’t go beyond 2 octaves.

Sheng: You almost need to see the exact model of Sheng the person is playing – the variety is endless (think like the 1700s when every church has a slightly different organ, here every player might have a different hand-held reed organ). Also, young players have not found the means to project the sound, rendering this section extremely soft when notated at the same dynamic). All said, this is a very important instrument to get right because it provides the necessary harmony to centre your music (i.e. you can’t really get Erhu to split into 3 groups to play chords). Nevertheless, in combined passages that’s ok as you can substitute with any western group.

Suona: Similarly, many COs have not move to chromatic suonas, and with the demands of a double reed, it’s very difficult to get their half hole notes in tune. There’s also an ensemble challenge here because Suona players can’t hear the rest of the orchestra very well when they play, coupled with their traditional role in the music (there’s no brass section, this is it) they tend to overpower any ensemble writing.

All the Huqin (Gaohu, Erhu, Zhonghu, etc.): Although they do best in lyrical passages, these instruments can be as versatile as a 1 string violin – so far the easiest way to put it. So if there’s a jump you won’t write for violin sul G, don’t do that to a Erhu; if there’s a pitch so high you won’t ask the violin to play sul G, don’t write that for Erhu.

Yangqin: some keys require great jumps across the table – watch for running passages. Otherwise, perhaps due to their placement in a orchestra so close to the conductor, they do serve as a good impulse provider for subdivision.

All the plucked strings (Liuqin, Pipa, Zhongruan, Daruan): Perhaps the hardest to write for because of their limited sound, a large section is required to project melodies. As with the rest, each instrument can have a lot of flare for solo passages, but as a group keeping in tempo is a great challenge. However, the tremolo harmonies worked really well in such combined groups for soft undulating passages.

Percussion: Probably the easiest to write for, check out special techniques, you might be surprised.

Ok thanks for reading.

Here’s 1/3 the orchestra and 1/2 the choir the work was originally scored for performing 4/5 of the 75 minute work .. still hoping for better recordings :/